While it's fairly common to change interest rates during an election year, it's rare to start a whole new cutting cycle right before an election.

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) on September 18 cut its base interest rate for the first time in four years.

The move marks the last time the US financial system has initiated an easing cycle ahead of a presidential election in nearly half a century.

While interest rates are rarely held steady in election years, the launch of a new easing cycle less than 10 weeks before an election has only happened twice before, in 1976 and 1984.

As an independent agency, the Fed, under the leadership of Chairman Jerome Powell, has consistently maintained that political factors, including election timing, do not influence its decisions on interest rates.

“This is my fourth presidential election at the Fed,” Mr. Powell said in a press conference after the Fed’s policy meeting in late July. “Anything we do before, during or after the election is based on the data, the outlook and the balance of risks, not on any other factors.” However, not everyone believes that.

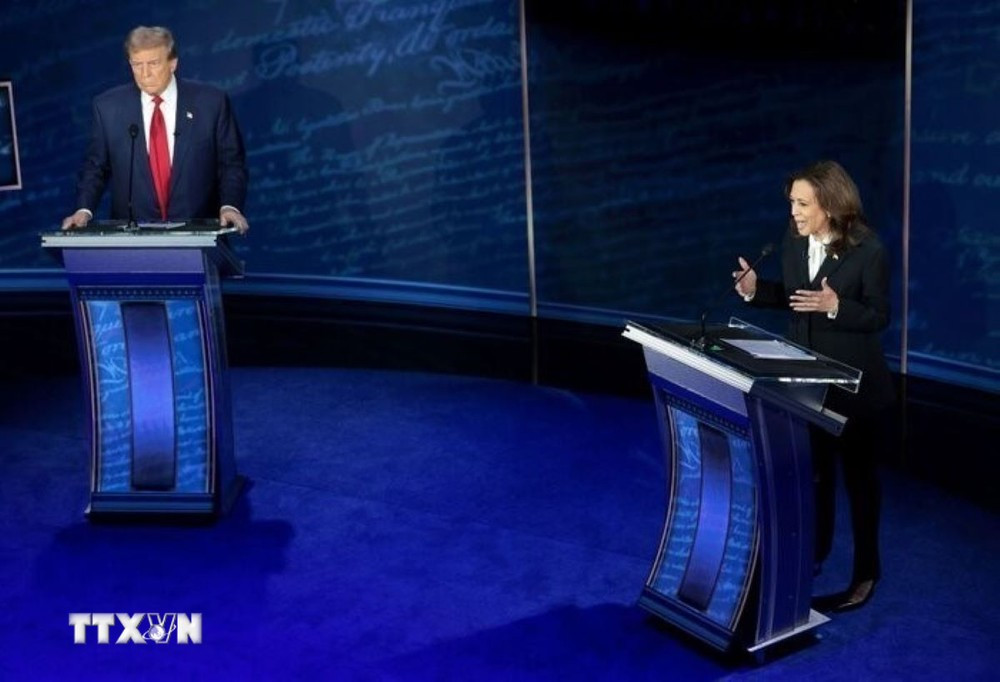

Earlier this year, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump suggested that the Fed could lower interest rates to support Democrats in the November 5 election. Trump even suggested that presidents should have the power to intervene in the Fed’s decisions.

Meanwhile, Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential candidate, has only vowed to respect the Fed's independence. "As president, I will never interfere with the decisions that this institution makes," she said last month.

Since 1972, the Fed has changed rates in all but two election years, and the decisions have been evenly split between increases and decreases. Rates have risen in five election years and fallen in six. But in most cases, these changes have been part of cycles that have been established for a year or more before the election.

In the five years that rates were adjusted up before the election, the incumbent president or party in power in the White House was re-elected four times. The exception was in 2000, when Democrats lost the election and former President George W. Bush and the Republicans won. At that time, rates rose by 1 percentage point from January to October under Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, with the last increase coming in June, about five months before the election.

Meanwhile, the incumbent president and his party lost five of the six elections held during years when interest rates were cut. The exception was 1996, when President Bill Clinton was re-elected to a second term. Rates, again under Chairman Greenspan, fell 25 basis points between January and the election, although the last cut came early in the year.

In 1984, under Chairman Paul Volcker, the Fed made its largest interest rate increase in an election year, 2.56 percentage points, to control the remnants of high inflation. As a result, President Ronald Reagan was re-elected in a landslide.

The only two presidential election years since 1972 that did not see a change in interest rates were 2012 and 2016. In 2012, Barack Obama was re-elected, and in 2016, Republican Donald Trump won.

While it's fairly common to change interest rates during an election year, it's rare to start a whole new cutting cycle right before an election.

Before the Fed's announcement on September 18, there had been four such cycles since the 1970s, and in three of them, incumbent presidents and parties in power lost.

The most recent example is the 2020 presidential election. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed under Mr. Powell cut interest rates twice in March by a total of 1.5 percentage points, bringing them to near zero. That year, Democratic candidate Joe Biden defeated Mr. Trump by a very narrow margin.

TB (summary)