Haunted by the memory of 42 dead Vietnamese soldiers buried in a bomb crater during a 1968 battle in Binh Duong, Australian veterans have returned to search for them for more than 20 years.

56 years ago, Brian John Cleaver left his homeland to fight with the allied forces in the South Vietnam battlefield, belonging to the 3RAR Battalion (3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment). The 20-year-old young man thought simply to go and complete his two-year military service and then return.

"I did not expect to be sent into a life-and-death, unjust war," the veteran recalled. On May 24, 1968, Brian's unit was deployed to establish and protect the FSPB Balmoral military base in Binh My commune, Tan Uyen district, Binh Duong. The base, about 40 km from Saigon, was considered one of the important battlefields to prevent the Tet Offensive and Uprising (phase 2) of the Liberation Army.

At the same time, the 7th Division, codenamed "Construction Site 7", one of the first main military units on the Southern battlefield, received orders from the Southern Command to attack this base.

The ensuing battles caused heavy losses on both sides. Brian was shocked to see the bodies of about 42 North Vietnamese soldiers being pushed by bulldozers into bomb craters, becoming mass graves.

The horrific experiences of the battle left him with post-traumatic stress disorder. For more than 30 years after his discharge, Brian tried to hide his illness and his past, using many high doses of medication but his condition did not improve but became worse.

"I was tormented and haunted that the grave would not be known to anyone. Their relatives would be heartbroken," the veteran said.

In 2002, Brian decided to return to Vietnam, to find the graves of soldiers on the other side of the battle line, hoping to heal his psychological wounds. As a tourist, he went to the old battlefield, which was now a vast rubber forest. Having narrowed down the area, the veteran returned to the country to collect documents and connect with his old comrades, including Private John Bryant.

"At that time, I really didn't want to mention the word Vietnam because it was too haunting," John Bryant recalled. Like Brian, John only thought of going to Vietnam as a young man's military duty. The 22-year-old man loved the scenery so he always carried a camera with him, ready to capture the beautiful moments of life.

John's 3rd Battalion was stationed in Nui Dat (Ba Ria - Vung Tau), but was often sent to reinforce some bases. However, before the night of May 25, 1968, John had never participated in a battle. "We were often dropped by helicopter into the forest with water and dry food, then depending on the location, we walked, crawled, crawled... and took souvenir photos," John recalled. Therefore, the battles in Binh My "were truly beyond the imagination" of young men like John at that time.

In the battle on the morning of May 26, 1968, Vietnam lost 6 people, Australian soldiers used shovels to dig holes to bury them. The fighting that followed two days later was more fierce, when 28 North Vietnamese soldiers died, all their bodies were pushed into bomb craters, bulldozers flattened them. Many of John's comrades were also killed and injured. The horrifying memories haunted him so much that he refused Brian's offer to return to Vietnam to find the old mass grave, only supporting by providing some still-archived images.

With the documents collected, the following year Brian returned to the old battlefield and dug himself. The fact that a Westerner was rummaging through the rubber plantation day after day attracted the attention of the people, and the militia of Binh My commune reported it to the district and then the province.

Lieutenant Colonel Le Hoang Viet, then Head of the Policy Department of the Binh Duong Provincial Military Command, in charge of collecting martyrs' graves, knew English so he was assigned to contact Mr. Brian.

"At first, Brian did not dare to say he was looking for a grave, but instead used the excuse of visiting an old battlefield," Colonel Viet recalled. However, after learning that the Vietnamese side also wanted to collect the remains of martyrs, Brian made his purpose clear. Colonel Viet accompanied the veteran for more than a decade. Every year during the dry season (from December to April of the following year), Brian also returned to Binh My, using his own money to hire workers, excavators, bulldozers, radar detectors, and survey several hectares of rubber to find graves.

In 2005, the Australian Department of Defense, through the Australian Embassy in Vietnam, sent to the Binh Duong Provincial Military Command two maps with coordinates of two mass graves of Vietnamese soldiers who died in the battle on the morning of May 28, 1968, when attacking the Balmoral military base.

The Binh Duong Provincial Military Command organized eight searches over an area of over 90 hectares in Binh My and Hoi Nghia communes, Bac Tan Uyen district (Tan Uyen later split into a district and a city), using various methods such as digging with hoes, shovels and excavators, studying maps, and using radar waves combined with satellite images. However, after eight searches, only one set of martyrs' remains was found.

According to Colonel Viet, after many fruitless searches, many people wanted to give up, but Brian persisted. One time, the search team dug 4 meters deep but found nothing, so they were forced to stop, making the veteran very sad.

The search did not yield the expected results, but Brian's determination gradually changed his comrade John Bryant. In 2007, after nearly 40 years, Private John returned to Vietnam.

"The openness, friendliness and putting aside the past of the Vietnamese people and government influenced me," John said. This made him return to Vietnam many times after that. In 2009, the veteran participated in searches for Brian's grave as an observer, occasionally giving advice when the digging was fruitless.

John said he had told Brian many times that he had identified the wrong location. Because on the night of the battle, he was on guard duty and had taken photos around the battlefield, he was sure that the burial pit must be 400-500 meters away from where Brian was looking. The identifying feature was a gun emplacement, from this point go straight ahead about 70-80 meters.

According to Lieutenant Colonel Le Hoang Viet, John's assessment was correct but was ignored at that time. The reason was that the search team trusted the existing documents too much, and John only participated as Brian's friend.

By 2019, after exhausting all his efforts, digging and searching over several hectares of rubber, Brian decided to stop the search. "At that moment, he cried and said: I'm sorry for everything," Lieutenant Colonel Le Hoang Viet recalled.

The search for the mass grave seemed to have come to an end, but John disagreed. "I prepared all the documents and knocked on many doors to continue the work my comrades left behind," the veteran said. According to him, the Australian Embassy was initially hesitant because the Vietnamese side had spent a lot of effort searching with Brian for 16 years.

However, when John presented evidence and explained that the excavation site had long been just a gathering place, a fighting position, the burial pit must be half a kilometer away. Convinced, the parties continued to support. This time, John was assisted by Luke Johnston, the son of an Australian veteran who had fought in Vietnam.

Luke was 43 years old at the time and had lived in Vietnam for 10 years. His father, a former soldier, had suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder like Brian. As a child, Luke had witnessed his father crying and being scared of fireworks. When he reached adulthood, his father told him about his time in Vietnam and his past traumas. In order to heal his father's wounds, he had sought out almost all the relevant information.

In 2009, Luke went to Vietnam for the first time. During two months traveling around the S-shaped country by motorbike, meeting many friendly people and beautiful landscapes, he recorded videos and sent them to his father. His excitement gradually relieved Luke's father's psychological burden. Since then, he has returned every year.

After his father passed away in 2016, Luke decided to stay in Vietnam and took a purely Vietnamese name - Luc, continuing to learn information related to his father's unit. During this time, Luke met John and agreed to join him in searching for mass graves of North Vietnamese soldiers.

In 2020, John was preparing to go to Vietnam to continue his search, but the Covid-19 outbreak and travel restrictions forced him to postpone his plans. At this time, Luke went to Binh Duong alone to rent a house and drove his motorbike to Binh My for many months. With his knowledge of data collection, combining John's evidence with modern equipment, Luke found the gun emplacement that John often mentioned.

"I told John right away, it felt so good," Luke said. From this position, Luke asked Glen Hines, an American expert in searching for missing soldiers in war, to reconfirm the coordinates.

After the travel was normal, John immediately went to Vietnam and the team members completed the report and sent it to the Australian Embassy. At the end of last year, the location of the mass grave of martyrs was determined in Choi Dung hamlet, Binh My commune, Bac Tan Uyen district, Binh Duong.

After Tet, from March 13, the Steering Committee 515 of Binh Duong province (searching and collecting martyrs' remains) organized the 9th search. After more than 20 days, the force discovered about 20 martyrs' remains and relics, some of which had the names of the martyrs engraved on them. Thus, after more than two decades, from veteran Brian's intention and the efforts of many parties, the mass grave was found, helping many families find their relatives.

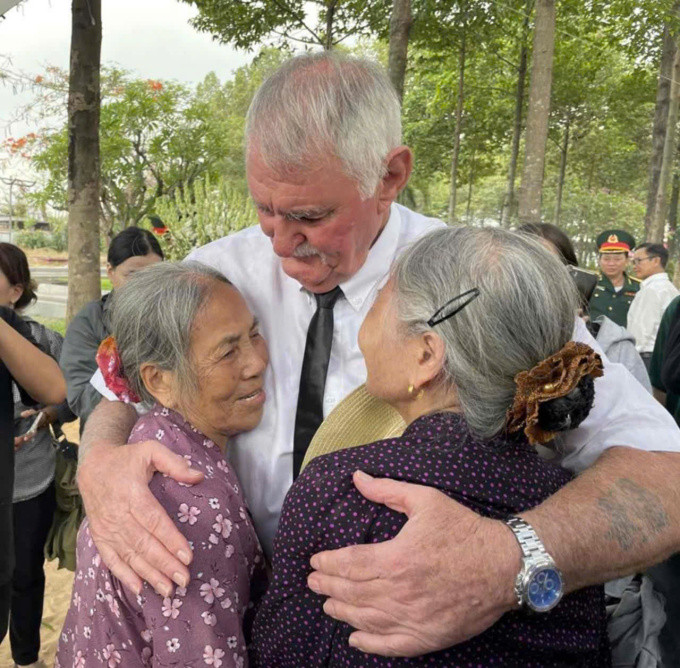

On April 26, the Binh Duong People's Committee held a memorial service for 20 martyrs in the anti-American resistance war at the provincial martyrs' cemetery. The ceremony was attended by former President Nguyen Minh Triet, the Australian Embassy, foreign veterans who fought in Vietnam and relatives of the martyrs. At the ceremony, local leaders highly appreciated the help of Australian veterans who have participated in the search for more than 20 years.

"I was really moved at the memorial service and felt that what I did was meaningful," Luke said. With his expertise in data collection, he plans to continue supporting organizations searching for the remaining graves. Meanwhile, Brian and John, veterans haunted by the battle, have found some comfort.

TB (according to VnExpress)